So quickly upon arriving in Ahmedabad one thing struck me, ‘I am off the tourist route now Hugo.’ Even Udaipur was a step down on the touristy scale from the golden triangle route, but Ahmedabad was nearing the bottom of the scale. The first obvious sign was when I exited the station and everyone stopped and stared at me. Okay, it wasn’t that bad. But I have been stared at a lot and I’ve seen a huge increase in the number of people wanting selfies. This sort of attention I don’t really mind, it’s much better than the tuktuk drivers hassling me for sure.

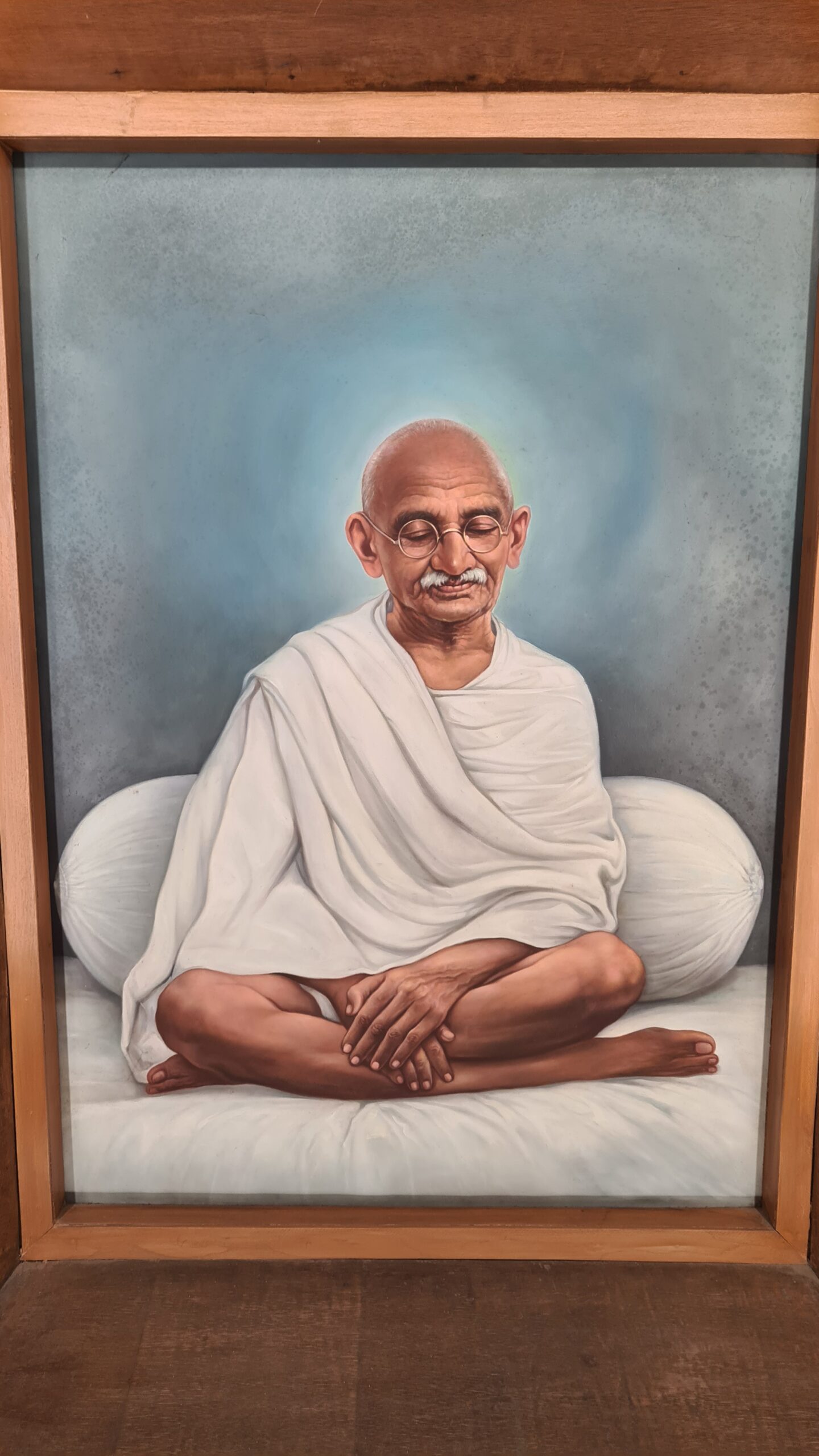

So why have I come to Ahmedabad? Well the honest answer is it was a convenient stop on my route south, but also there was one site I did want to see… Gandhi’s Ashram, where he lived and ‘lead’ a commune type facility from 1915 to 1933. The Ashram has now been converted into a museum dedicated to Gandhi’s life which was fascinating, and left me feeling very, well, enlightened.

Firstly, impressive bloke that’s for sure. I kinda knew his gist – pacifist etc, but actually there was so much I didn’t know about him. I’ll run over a bit of Ghandi then move onto Ahmedabad, I’ll also cover a significant, unexpected and last minute change to my plans – and the weirdest experience I’ve had in India so far.

So Gandhi – brief history / my major takeaways:

- The first entry in Gandhi’s timeline listed by the museum was that during his school examinations, his teachers told him to copy the answers from the other students but he refused. Allegedly.

- He got married at age 13 to Kasturbai, presumably an arranged marriage.

- Upon completing school, he sailed to England to train as a barrister. He wrote home many times feeling very out of place in London, and didn’t generally seem to have a good time. If anything evidenced this more than his letters, was the fact he passed his law exams and was called to the bar on the 12th June 3 years after arriving and sailed home the next day.

- He then also spent a period of time in South Africa and experienced quite a bit of racism, where he found that because he was Indian he didn’t have rights. South Africa also became the beginnings of his social-activism. Protesting Rosa Parks style getting kicked off a first class train carriage. He also established a political organisation in South Africa to agitate for Indian rights. His work is picked up across international news outlets.

- The South African Government introduces a law requiring all Indians to register to their local government, and this is where Gandhi first implements his satyagraha strategy. A practice of ignoring the law and accepting (or inviting even) the punishments. He was subsequently imprisoned several times but eventually the law was abolished.

- During the Boer wars Gandhi set up and volunteered in the Indian Ambulance Corps, which he was later awarded a medal for by the British.

- Now experienced from his time in South Africa, it was time to take up the good fight back home in India (although fight definitely isn’t the right word here). This time against, you guessed it, British rule. He sets up his Ashram during this time, as his base of operations.

- Gandhi becomes the leader of the Indian National Congress party and campaigns for Indian self-rule (aka independence). In typical Gandhi style, he subsequently launches a non-violent non-cooperation campaign against Britain. Crucially urging Indians not to buy British goods specifically cloth (in favour of spinning their own) but also rejecting British government and authority. Very unimaginatively the British then imprisoned him from 1922 to 1924. His trial however was fascinating reading (full transcript here), it became known as the Great Trail.

The Great Trail – a brief retelling

- Gandhi pleads guilty to sedition. Essentially the case is based on his writings urging non-cooperation. Also on trial is the someone who helped Gandhi print / distribute these.

- Given the guilty pleas the judge decides not to try the case, instead moving straight to sentencing. A decision Gandhi smiled at.

- Ghandi is given the opportunity to speak before sentencing:

- “…I had either to submit to a system which I considered had done an irreparable harm to my country, or incur the risk of the mad fury of my people bursting forth when they understood the truth from my lips. I know that my people have sometimes gone mad; I am deeply sorry for it. I am, therefore, here to submit not to a light penalty but to the highest penalty. I do not ask for mercy. I do not ask for any extenuating act of clemency. I am here to invite and cheerfully submit to the highest penalty that can be inflicted upon me for what in law is a deliberate crime and what appears to me to be the highest duty of a citizen.”

- “In the past, non-co-operation has been deliberately expressed in violence to the evil-doer. I am endeavouring to show to my countrymen that violent non-co-operation only multiplies evil and that, as evil can only be sustained by violence, withdrawal of support of evil requires complete abstention from violence. Non-violence implies voluntary submission to the penalty for non-co-operation with evil. I am here, therefore, to invite and submit cheerfully to the highest penalty that can be inflicted upon me for what in law is a deliberate crime and what appears to me to be the highest duty of a citizen.”

Now I’ve missed out huge sections here, about the British oppression and the wrongs of colonial rule. I don’t so much want to dive into it, I don’t think I know anywhere near enough for one, but I think we can all agree it was wrong, pretty terrible really. I’m much more keen to give you a sense of Gandhi the man.

- His friend added: “I only want to say that I had the privilege of printing these articles and I plead guilty to the charge. I have got nothing to say as regards the sentence.”

- It was then time for the Judge’s sentencing, he started with:

- “Mr. Gandhi, you have made my task easy in one way by pleading guilty to the charge. Nevertheless what remains, namely, the determination of a just sentence, is perhaps as difficult a proposition as a judge in this country could have to face. The law is no respecter of persons. Nevertheless, it will be impossible to ignore the fact that you are in a different category from any person I have ever tried or am likely to have to try. It would be impossible to ignore the fact that, in the eyes of millions of your countrymen, you are a great patriot and a great leader. Even those who differ from you in politics look upon you as a man of high ideals and of noble and of even saintly life.”

- His sentence was 6 years imprisonment, the judge also made a comparison to the trial (and imprisonment) of Bal Gangadhar Tilak. [Which I’ll leave has further reading for any of you keenos out there]

- Gandhi responded “I would say one word. Since you have done me the honour of recalling the trial of the late Lokamanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, I just want to say that I consider it to be the proudest privilege and honour to be associated with his name. So far as the sentence itself is concerned, I certainly consider that it is as light as any judge would inflict on me, and so far as the whole proceedings are concerned, I must say that I could not have expected greater courtesy.”

NB: the quotes and general record here have been taken from an edition of Young India (published by Gandhi at the time). Disclosing in the interest of transparency. For what it’s worth I reckon it’s fairly accurate, especially given Gandhi’s whole MO. And anti-Gandhi sources are hard to find.

Returning to the timeline…

- Gandhi is released after two years of his sentence, and has this to say “My release has brought me no relief. Whereas before release, I was free from responsibility, save that of conforming to goal discipline and trying to qualify myself for more efficient service, I am now overwhelmed with a sense of responsibility, I am ill-fitted to discharge…”

- However, despite his doubts he continues his drive for non-violent social activism. Which brings us to his likely most famous satyagraha campaign.

- The British introduced the Salt Act of 1882, which prohibits Indians from collecting or selling salt, their salt, from their salt plains. This meant Indians would have to buy it off the British with a tax included. Gandhi saw this as a direct attack on Indians but in particular the poorest Indians, with salt being a crucial part of their diet. He led tens of thousands of Indians on a 240 mile march from his Ashram in Ahmedabad to the salt fields to illegally collect their own salt. Over 60,000 people were arrested, but Gandhi eventually ironed out a deal with the British Viceroy. Agreeing an end of the satyagraha in exchange for the release of the prisoners and the end of the Salt Act. Another successful non-violent protest – the points are stacking up in Gandhi’s favour.

- Later under a different Viceroy Gandhi is imprisoned again. I’m not sure for what. While imprisoned, in opposition to a new policy, formally segregating the lowest class of people in India (known as untouchables) within the constitution, Gandhi starts an indefinite fast. This causes enough upheaval across India for the British to change the policy.

- Again ten years later, Gandhi was imprisoned again.

- Finally, after all of his struggle and that of countless others, India achieves independence in ‘47. Although as a result of the partitioning of the sub-continent (into the likes of India and Pakistan etc) riots erupt between Muslims and Hindus. What does Gandhi do? He fasts once again until the rioters pledge peace, which they do.

- Shortly after world war two Gandhi was assassinated by someone angered by his efforts to reconcile Hindus and Muslims.

So that is a very brief and very crude overview of Gandhi timeline if you will. But he galvanised the people of India through the nobelist means, preaching non-violence and a complete dedication to the truth.

I’ll conclude this Gandhi section with a few interesting bits and bobs. Including some more of Gandhi’s own words and some words about him from notable others:

During the satyagrahi protests (where they would break the law and willing surrender themselves to the punishment), the participants were bound by a set of rules while imprisoned – which were as follows:

- To act with the most scrupulous honesty;

- To cooperate with the prison officials in their administration;

- To set by our obedience to reasonable discipline an example to co-prisoners;

- To ask for no favours and claim no privileges which the meanest of prisoners do not get and which we do not need strictly for reasons of health;

- To ask for what we need and not to get irritated if we do not obtain it; and

- To do all the tasks allocated to the utmost of our ability.

“I do not believe in the doctrine of the greatest good of the greatest number. It means in its nakedness that in order to achieve the supposed good of 51 percent the interests of 49 percent may be, or rather, should be sacrificed. It’s a heartless doctrine and has done harm to humanity. The only real, dignified human doctrine is the greatest good of all, and this can only be achieved by uttermost self-sacrifice.” Gandhi, 1932.

“I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet.” Gandhi, 1921.

“Generations to come, it may be, will scarce believe that such a one as this, ever in flesh and blood, walked upon this earth.” Alby Einstein, about Gandhi.

“The essence of lying is in self-deception, not in words; a lie may be told by silence, by equivocation, by the accent on a syllable, by a glance of the eye attaching a peculiar significance to a sentence; and all these lies are worse and baser by many degrees than a lie plainly worded.” John Ruskin

An extract from the start of the observances of Gandhi’s Ashram:

“The object of this Ashram is that its members should qualify themselves for and make a constant endeavour towards the services of the country not inconsistent with universal good.

The following observances are essential for the fulfilment of the above object.

- Truth. Truth is not fulfilled by mere abstinence from telling or practising untruth in ordinary relations with fellowmen but truth is God, the one and only reality. All other observances take their rise from the quest for and the worship of truth. Worshippers of truth must not resort to untruth, even for what they may believe to be the good of the country, and they may be required, like Prahlad, the civility to disobey the orders even of parents and elders in the virtue of their paramount loyalty to truth.”

“You have to realise that the power of unarmed non-violence is any day far superior to that of armed force… I have been preaching the creed of non-violence for 50 years… If the method of violence takes plenty of training, the method of non-violence takes even more training, and that training is much more difficult than the training for violence.” Gandhi 1938

Okay so that’s Gandhi. On whom I had quite a lot to share, however, thankfully, I have less on Ahmedabad. But if you do want more from Gandhi then here are his complete works volume 1 to 98.

From my brief stay, Ahmedabad did seem like a very authentic Indian city, and one with its own little gems scattered throughout.

Firstly, there was the Hutheesing Jain Temple. A stunning building, completely covered with beautiful decorative carvings. The detail was outstanding, and carried through to the inside (although no photos were allowed inside). Within was a courtyard holding the main temple structure in the middle, and surrounded by shrines behind small doors. The shrines held smallish idols with wide-set gemmed eyes, which were a bit spooky illuminated only by the small windows in the doors. But the place was a peaceful retreat within the city and relatively empty.

The second was the street food market found in the middle of the city. The market started at 8pm and was a few streets filled with stalls with various sitting areas between them. The first day I visited it was dry and the seating was large mats on the floor. The second day it had started to rain and the stalls started erecting tarps very haphazardly to provide a sheltered area with tables. Men climbed various ladders and poles to erect this shelter, and the number of multi-point extension cables I saw getting rained on was concerning. Neither day did I know what I was ordering but it was tasty (and carb heavy) on both counts.

On my final day, I was heading further south to Mumbai. However my departure from Ahmedabad was less than smooth. I spent most of my day mincing around the various markets and taking it all in, waiting for my 5pm train. I got to the station around 4.30, only to realise my 5pm train was a 3pm train… Whoops!

I forgot the golden rule of travelling with Hugo. I’m an idiot and shouldn’t be trusted.

So it was finding an alternative route time. This is where the Indian railway can bite back a bit, whereas in the UK you’re competing with c60 million people for train tickets, here you’re up against over a billion and the railways are the way to get around (cheap, reliable and more comfortable than the roads). So all of the trains were booked out for days in advance. I eventually found an indirect route to Mumbai, but upon researching Mumbai some more I decided I didn’t want to go. Most notably to get around Mumbai you use the local train network, which I believe is the deadliest train network in the world. Very overcrowded, with people taking to the roof etc. I’d also had enough of the cities so decided instead to find whatever route I could even further south.

In the end I found an overnight 15hr train east to Itarsi – a very very small city which sits on a major railway junction. And from Itarsi (after a 9hr wait) a 22hr train to Goa. The first leg was mostly fine, however an Indian man did, somewhat persistently, suggest we give each other mutual handjobs to pass the time. Fortunately I managed to get rid of him pretty quick, with some very firm (and even more persistent) no thank yous.

I made it to Itarsi, where I enjoyed some time in the park until it closed at 11am???? Not sure what that was about. If I thought Ahmedabad was low on the touristy scale, Itarsi was off the bottom of the chart. I stuck out so much, while sitting in the park a small crowd formed around me – ahah – all quite friendly though. For the rest of my time in Itarsi I found a couple of meals, and then waited at the station. This is where the journey became rougher. Firstly there was no air-con. But arguably worse, I felt a suspicious rumble in my stomach…

The timing of this was really unfortunate, with a 22hr train ride ahead. But this occurrence was inevitable. A question of when not if. Of course, I’m speaking of the Nile runs, Montezuma’s revenge. Simply put, Delhi Belly had hit. Now there are toilets on board the train (thank every god I think of) but the stomach cramps and general aches on the long train were pretty rough. After what seemed like days I did eventually reach Goa (and without any further sexual advances).

In Goa I’ve been recovering in a lovely, very bohemian hostel which has been very nice. The north of Goa where I am is quite party-y however the hostel is nice and chill – with the parties going on at a beach a few kms south. After the third day I did think I’d recovered but actually I don’t think I’m out of the woods quite yet.

Goa itself is close to a tropical paradise, littered with palm trees and endless beaches which enjoy beautiful golden sunsets. I can see why it’s a go to tourist spot among Indians and international travellers. This is at least from what I can tell from my very short excursions out of the hostel.

I have also decided that the south of India in March is too hot, and that I’d never get all the way south and then back up to some of the north-east I want to see. So tomorrow I’m flying north, to Assam. Both the increased latitude and altitude decreases the temperature by a good 10 degrees which will be very much welcomed. I’m hoping to see some wildlife, some mountains, the odd waterfall, and of course while in Assam – drink some tea.

Well that’s it for this special bumper dumper edition of the bog I mean blog.

Looks like Ghandi has made an impression on you. Hardly reflective of our politicians. Trump and Boris wouldn’t know the truth if it bit them. The adventure continues. We love the photos and your narrative, especially when it relates directly to you.

You are really packing a lot in.

I hope the Delhi belly rune it course soon. That’s miserable and makes you feel tired.

Anyway Hugo. Keep it going and keep it coming. Xxxx

Yeah he sorta did. Just a very impressive bloke. And yeah that couldn’t be more true – a politician seemingly acting in the interest of the people (or at least his perception of the people’s interests). Thanks Dad!! xx